Animation – We Can Do It!

- Mindy Johnson

- Mar 30, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 3, 2020

Indeed, we are living in strange and uncertain times. With family and friends in the medical field, the daily updates on the rising curve of this pandemic are rough. The devastating numbers leave us searching for logical voices beyond the federal absurdity, seeking resolutions to these dangerous shortages, and exploring new approaches for connection and comfort. We rejoice in a welcomed meme of levity on social media, or getting some valued FaceTime with a friend. Every bit helps with processing this new reality we are in the midst of.

As an historian, I've learned that there are times when it helps to — look to the past to enlighten the future. For me, this imposed "safer at home" reality brings focused time to write and to explore our animated past. As my research deepens, there is some comfort in discovering that since its inception, the animation industry has always risen to the times — serving and sustaining — throughout a wide range of pandemics and public health crises.

Winsor McCay's "How a Mosquito Operates" (1912) launched new horizons for the applications of this burgeoning medium. In a lost live-action prologue to the animation, a professor who understands these pesky critters, suggests McCay "make a series of drawings to illustrate just how the insect does its deadly work." McCay's hand-colorized short was highly received for the humor of a pesky giant mosquito, but he recognized the opportunity here for the application of animation within "...serious and educational work." Indeed, this clever short — comprised of a comic series of moving drawings — entertained, launched a wider understanding of how animation could be applied, and most notably enlightened audiences to the rapid spread of various diseases and infections via the pesky mosquito.

By 1918, World War I (WWI) was raging in Europe, when the Spanish Flu seized the world in the worst pandemic of the 20th century. Nearly one-third of the earth's population suffered, and over 50 million lives were lost. With most of the U.S. male population fighting overseas, women stepped up on the medical front lines to care for the sick and to bury the dead. Amid this devastating loss of life, the visual arts became a vital tool to convey the ravages of this disease as it spread across the globe.

Illinois State Board of Health Cartoon 1919

Public warning on the dangers of spitting, marking a dramatic decline in tobacco chewing

Moving women's health to the forefront as they attended the sick and dying in the U.S. Artists and illustrators rose to the call of this vital need for widespread understanding and awareness. From posters, notification flyers, and informative ads, the impact of this public health awareness was powerfully conveyed through the visual arts, but sadly, not without a dreadful toll.

The Forgotten Year of Death (1918) Fine artist Gustav Klimt suffered terribly and his protégé Egon Schiele captured the dread of Klimt's experience with this disease before both died from the pandemic. Painter Edward Munch explored the pain and isolation of the ravages of the Spanish Flu through his art. Thankfully, he survived, but the impact of this experience defined much of his later work.

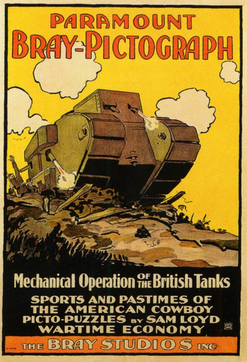

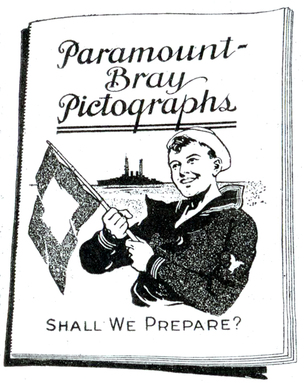

(above left) Egon Schiele – Gustav Klimt on his death bed (1918) (above right) Edvard Munch – Self Portrait with the Spanish Flu (1919) By 1918, as this deathly outbreak began, animation was a newly established industry spawned from comic arts, but it quickly became clear this was the logical platform to relay the facts and combat this public health struggle. The pioneering animation company Bray Studios stepped up with an entire division comprised of several units dedicated to developing and creating training and educational films during WWI. Working closely with the military, animated and motion picture programming was developed to widely teach the life-saving methods and importance of disinfectants, personal hygiene, quarantine measures, limiting of public gatherings, and the various steps necessary to stop the spread of this horrible flu. This combined demand of training films for wartime, and informative public health films to stop this pandemic, revealed a new outlet for films featuring animation. Bray Studios continued creating such films with animation which were widely circulated, including: How You See (2/16/20), How We Hear (4/4/20), How's Your Eyesight (5/14/20), How We Breathe (6/12/20), Action of the Human Heart (1920), and many more.

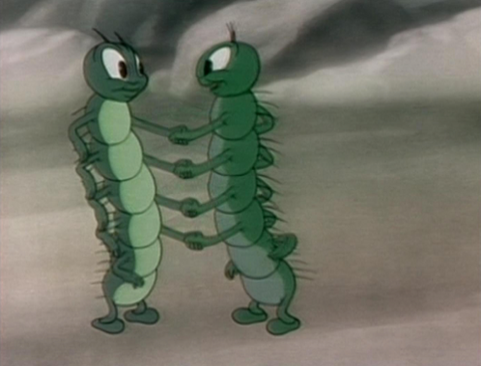

By the late 1930s and early 1940s, with U.S. troops once again heading overseas during World War II, public health found its way back into the forefront of the animated form. In addition to military training, mainstream animated short films featuring clever visual storytelling, demonstrated the need for public health awareness and the implementation of renewed responsibility with sanitary measures. An early short from Warner Bros. Studios entitled: Bug Parade (1940) humorously examines the wide world of entomology. The importance of proper hygiene is warned as the film's "common cootie" reacts to spotting a "U.S. Army Training Camp" sign by turning to the audience and gleefully announcing before dashing in — "Millions and millions of soldiers, and they're all mine!"

Training and Public Service films became a standard part of the animated offerings coming down the production pipelines at most studios. Walt Disney's 1943 training film Defense Against Invasion explores the importance of vaccination as "the doctor" conveys what can happen to a defenseless body overwhelmed by invading germs. Proper actions wisely result in "V for Vaccination and Victory!" Perhaps the most interesting "Public Service" Disney short The Winged Scourge (1943), has The Seven Dwarfs demonstrating the importance of defeating the ravages of malaria, spread via the monstrous mosquito.

The mosquito's impact on public health safety is also humorously, but effectively, explored in the 1940s Warner Bros. Private Snafu series: "It's Murder She Says" (1945). A story of a worn-out, outcast "Anopheles Annie – The Malaria Mosquito" reminisces about "the good-old-days" when she could roam wherever she wanted. Ultimately, it was parasitologists, entomologists, malariologists, and indeed..."every damn-ologist in the country" who finally tracked her down. With her infectious days behind her, she longingly cautions "a smart operator can still sneak-in a one-night stand." Such spicy language and scenarios were the exception to regular animated fare, but spoke directly to the targeted military audiences these shorts were created for.

Public health was chronically hit with polio epidemics breaking out across the country in the 1910s, 1930s and 1940s, but it wasn't until 1952 before Jonas Salk developed the first effective polio vaccine. Rigorous testing continued for nearly a decade before polio was finally combatted thanks to the Sabin vaccine. But to continue the fight, once again the animation industry answered the call — creating nationwide campaigns for fighting this virus and to develop the cure. This 1954 March of Dimes campaign featured some of animation's top celebs to draw vital awareness to this dreaded disease:

With television units entering homes at a record rate in the mid-1950s, this new technology opened opportunities for the use of animation to educate and the importance of public health was one of the lead subjects. Indeed, Pinocchio's constant-conscious cricket — Jiminy — rose to renewed stardoms with the charming "I'm No Fool," "You and Your...," and "The Nature of Things" series for television. These vital and entertaining shorts educated generations on their bodies, the world around them and the importance of good health practices.

Into the optimism of the late 1950s, pandemics and public health issues became merely plot-lines within our fairy tales, when in Walt Disney's 1959 classic "Sleeping Beauty," a kingdom-wide "shut-down" of sleep was cast by the good fairies to deflect the devastating impact of Maleficent's sinister curse.

The 1980s brought the ravages of the global HIV pandemic to the forefront, and the sweeping devastation of this scourge deeply impacted the animation industry. Brilliant artists who shaped some of the most memorable characters and landmark films of this time were lost. Most notably, the man who taught a Mermaid to sing and a Beast to love, Oscar-winning songwriter, Howard Ashman, lost his fight with this cruel virus.

Today, in this contemporary pandemic of COVID-19, many industries have completely ground to a halt in an effort to maintain safe social distancing. In an effort to flatten this ever-rising curve, production has completely stopped on sound stages, and on locations throughout Hollywood and around the globe. With no immediate end in sight, it's interesting to note, within one industry that understands the importance of "curves" and escalating "lines," animation continues — thanks largely to the advent of digital pipelines developed in the late 1980s. While this initial "streamlining" of the production process was intended to reduce production costs, it has now proved vital as artists — working from home while "sheltering in place" — are still moving via online platforms to ensure continued production within the industry of motion!

While the downward slope to the curve on this crisis is still unclear, and there may be more questions than answers these days, looking back through the pantheon of public health problems we have overcome can cast some hopeful light onto the road ahead. Since its inception, the animated art form has served to educate, enlighten and unload the worries of countless burdens along the way. Like the resilience of the human spirit, the artistry and application of animation continues to move — ever forward! We Can Do It! Stay safe everyone!

Comments